I

am re-reading A. Edward Newton’s The Greatest Book in the World and Other

Papers (1925) and the ghosts of bookmen past envelop me. Not only from the text of Newton’s

biblio-essays, but also from the copy itself—held gently, read closely, and

treasured by three ardent bibliophiles, each with their bookplate on the front

free endpaper and their scattered jottings crowding the rear pastedown. I see in the morning light the mild soiling on

the tan boards from their hands and fingers – bookish fingerprints. The front hinge is cracked but sturdy. Newton has added a humorous inscription to

the first owner. A carbon letter of the

owner’s reply to Newton is attached to the front free endpaper by a dainty paperclip. Tis’ a well-loved copy – a copy that affected

me emotionally when I catalogued it, surprising me in that respect for I have

many association copies and this would not rank among the greats in an

analytical sense. But then a yearning to

tell the book’s story. So let us begin.

The Greatest Book in the World and Other Papers was Newton’s third major book of essays following The Amenities of Book Collecting (1918), and A Magnificent Farce (1921). Newton as a writer, biblio-celebrity, and collector was at the peak of his powers in 1925. It is remarkable he was able to get any work or collecting done considering the sheer number of his various books he inscribed for fans and correspondence he responded to. But he loved it all and it fed his flame. The title essay of this work is a lengthy history of the Bible in printed form, highlighting the earliest, rarest, and most important editions. Newton explores other collecting areas in “Colored-Plate Books,” and “Sporting-Books.” There is much on London and Newton’s beloved 18th-century of Samuel Johnson and related writers. He also writes of Dicken’s A Christmas Carol in “The Greatest Little Book in the World,” and ends with a touching homage to his friend and mighty American collector Beverly Chew in “The Last of His Race.” Most of the essays have aged well and Newton’s engaging style draws in the reader quickly and usually holds them. An abundance of illustrations add interest.

This copy is presented to its first owner, “Inscribed for a lawyer Mr. M[ark]. G. Holstein – but not a criminal – I hope. (see page 37). A. Edward Newton, Nov. 30, 1925.” The page referred to cites the passage: “And I wish that trials for ‘heresy’ might cease – those tragic farces at which kindly old men of excellent character are goaded and made miserable by criminal lawyers—what a happy phrase that is!—at the instance of other old men.”

Tipped to front free endpaper is a humorous carbon copy reply dated Dec. 8, 1925 from Holstein to Newton thanking him for inscribing the book (“I have received from Mr. [Charles] Sessler my copy of ‘The Greatest Book in the World’”), chastising him for making fun of lawyers (“I forgive you, both because of the pleasure which your book has already given me and the pleasure which I still anticipate”), and expressing his appreciation for Newton’s writings (“My introduction to the author dates from the time when I first ran across the his papers on the ‘Amenities’ in the Atlantic, I may. . . say that ‘while my debt to him can be acknowledged it can never be paid’”). Mounted to the rear free endpaper by Holstein is a Feb. 25, 1927, column “Notes on Rare Books” reviewing Essays and Verses About Books by the late Beverly Chew – the collector eulogized by Newton in the book.

Already the book has gotten my full attention. For the book has been in the hand of Newton, of course, but also has passed through his friend and noted Philadelphia bookseller Charles Sessler (whose assistant Mabel Zahn was an ardent Newton collector). But what of Holstein? To proactively seek out not merely a signed copy but a personally inscribed copy and then write a reply to the author indicates advanced symptoms of the gentle madness.

I dig and find Mark G. Holstein (1873-1952), a New York lawyer, who published a number of biblio essays on various topics. Notably, he contributed to The Colophon New Series, Vol. II, No. 4, 1937, “A Five-Foot Shelf of Literary Forgeries.” In The Colophon “Notes on Contributors” we read, “Mark Holstein is president of the Quarto Club. He describes himself as an aging lawyer, who started collecting books in his teens and has kept it up with unflagging zeal for almost fifty years. He has collected more books than he will ever be able to read, and has a separate room devoted to Shakespeariana. If all the time he has spent in reading and marking [auction / bookseller] catalogues were placed end to end, it would reach far enough to round out several college careers.”

Then a little voice talks to me, a faint recall, and I look in my own library catalogue and behold! I find I have Holstein’s pamphlet The Diversions of a Will Collector (1929), a paper read to the Quarto Club in New York City, this copy inscribed to none other than legendary bookseller A.S.W. Rosenbach, “To Dr. R, with the season’s greetings and the compliments of the author.”

The association copy excitement I’m feeling now is rising quicker than my homemade pizza dough. There is more to explore with Holstein. I find a photograph of his library illustrated in another issue of The Colophon; I want to know about the Quarto Club he founded; I want to read more of his writings, but such byways will be pursued later. For now, this enthusiastic original owner of The Greatest Book in the World has been rediscovered if not fully resurrected. As to the dispersal of his library, the New York Times obituary of Oct. 19, 1952 records, “His will provides for distribution of his library among various public libraries.” I also discover that “The Fine Library of Mark G. Holstein, Attorney at Law, New York City,” was sold by Swann Galleries in 1953. I have yet to see its contents.

But I can hazard a guess that at Holstein’s sale, if not earlier, Montgomery Evans II (1901-1954), the second owner of the book, acquired this copy. His bookplate is neatly placed under Holstein’s. Montgomery Evans collected British author Arthur Machen with fervor as Vincent Starrett records in his autobiography, Born in a Bookshop. I find references elsewhere to Evans’ collection of Anglo-Irish writer Lord Dunsany. Evans knew Machen personally and wrangled letters and manuscript material from his favored authors. His ownership of this book was apparently a short-lived union, however, for Evans died in 1954, only a year after the Holstein auction. But his time spent was a memorable experience. In faint pencil on the rear pastedown Evans was moved to record and initial the following, “Read with great pleasure on Sundays in New York, May 1953.” This simple note touched me. Could Newton have asked for a more concisely satisfying review?

From Evans the book found its way into the library of Abel Berland (1915-2010), a Chicago real estate magnate, who as young Jewish man experienced discrimination and hardship, yet in Horatio Alger fortitude garnered a law degree and rose to the heights of business. Berland collected an exceptional library of English literature, incunabula, science, and philosophy. The highspots of this collection, including a fine set of the Four Folios of Shakespeare, were auctioned by Christies in October 2001 and brought $14,391,678. (The books would have certainly sold for even more had the events of 9/11 not happened shortly before the sale.) Yet Berland’s collection contained many more books than his expensive rarities. By all accounts, he loved to deep-dive into the history and scholarship of his collection, and he was a voracious reader of biblio-books. This provided inspiration and gave him a sense of place in the long history of book collecting.

Berland was devoted to Chicago’s The Caxton Club, a highly regarded organization of bibliophiles established in 1895. Berland serving a term as president and recruited many new members. He was frequently featured in the Club’s journal, the Caxtonian. After his death, the April 2011 issue of the Caxtonian was dedicated to Berland and contained many reflections by people who knew him well.

Fellow collector R. Eden Martin remembered Berland’s friendship and guidance, “Abel Berland was Chicago’s greatest book collector. Others have magnificent collections and are outstanding scholars in their fields. But Abel brought together wonderful books from a wide variety of literature and thought: copies of masterpieces of English literature. . . books from the early years of printing with movable type, and books of science and intellect. . . .”

“Abel would tell how as a child, after his parents had told him to turn out the light and go to sleep, he would read in bed with a special light. Or how, as a young man, he would bring home a book in its wrappings and place it outside a window in his house, so he could smuggle it in without having to provide an explanation. . . .”

“Abel introduced me to two prominent American dealers. He set up a lunch for me with a handful of Chicago’s notable collectors. He regularly sent me copies of pages from auction catalogues. He spread his enthusiasm like a virus, which in a way it was. He helped me grow from an accumulator into a collector.”

Robert Cotner, another close friend, recalled a particular visit, “The [library] room,” Abel said that day, “is my library of the mind, the habitation of books literary, scientific, and historical that I consider important. I often read into the night and am stimulated by the great ideas of these remarkable people.”

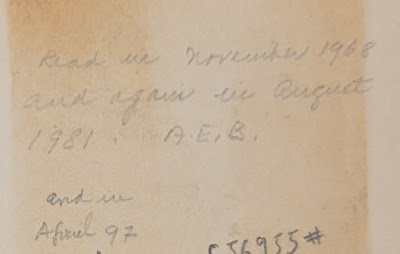

The ample bookplate of Abel Berland in Newton’s The Greatest Book in the World largely covers—nay, overshadows—the earlier Holstein and Evans bookplates. It features a photograph captioned, “A Frank Lloyd Wright designed bridge as viewed from our library window.” Heady stuff, but did Berland really read the book as he enjoyed the view? Did he spend time with it as Holstein and Evans had and draw biblio-nourishment from the contents? I wondered as much as I closely examined the book. The answer came on the rear pastedown, just below Montgomery Evans’ faint penciled note, Berland had added his own, “Read in November 1968, and again in August 1981, and in April 97.”

I then began my own re-reading that bright morning, holding the book as the others before me, pausing occasionally to view our spring yard in bloom with fresh foliage courtesy of Nicole’s efforts, the sharp sounds of birds and squirrels, and the focused efforts of our new cat, Ziggy, doing his best to hunt them, and realizing it was not unlike my pursuit of books.

The Greatest Book in the World and Other Papers was Newton’s third major book of essays following The Amenities of Book Collecting (1918), and A Magnificent Farce (1921). Newton as a writer, biblio-celebrity, and collector was at the peak of his powers in 1925. It is remarkable he was able to get any work or collecting done considering the sheer number of his various books he inscribed for fans and correspondence he responded to. But he loved it all and it fed his flame. The title essay of this work is a lengthy history of the Bible in printed form, highlighting the earliest, rarest, and most important editions. Newton explores other collecting areas in “Colored-Plate Books,” and “Sporting-Books.” There is much on London and Newton’s beloved 18th-century of Samuel Johnson and related writers. He also writes of Dicken’s A Christmas Carol in “The Greatest Little Book in the World,” and ends with a touching homage to his friend and mighty American collector Beverly Chew in “The Last of His Race.” Most of the essays have aged well and Newton’s engaging style draws in the reader quickly and usually holds them. An abundance of illustrations add interest.

This copy is presented to its first owner, “Inscribed for a lawyer Mr. M[ark]. G. Holstein – but not a criminal – I hope. (see page 37). A. Edward Newton, Nov. 30, 1925.” The page referred to cites the passage: “And I wish that trials for ‘heresy’ might cease – those tragic farces at which kindly old men of excellent character are goaded and made miserable by criminal lawyers—what a happy phrase that is!—at the instance of other old men.”

Tipped to front free endpaper is a humorous carbon copy reply dated Dec. 8, 1925 from Holstein to Newton thanking him for inscribing the book (“I have received from Mr. [Charles] Sessler my copy of ‘The Greatest Book in the World’”), chastising him for making fun of lawyers (“I forgive you, both because of the pleasure which your book has already given me and the pleasure which I still anticipate”), and expressing his appreciation for Newton’s writings (“My introduction to the author dates from the time when I first ran across the his papers on the ‘Amenities’ in the Atlantic, I may. . . say that ‘while my debt to him can be acknowledged it can never be paid’”). Mounted to the rear free endpaper by Holstein is a Feb. 25, 1927, column “Notes on Rare Books” reviewing Essays and Verses About Books by the late Beverly Chew – the collector eulogized by Newton in the book.

Already the book has gotten my full attention. For the book has been in the hand of Newton, of course, but also has passed through his friend and noted Philadelphia bookseller Charles Sessler (whose assistant Mabel Zahn was an ardent Newton collector). But what of Holstein? To proactively seek out not merely a signed copy but a personally inscribed copy and then write a reply to the author indicates advanced symptoms of the gentle madness.

I dig and find Mark G. Holstein (1873-1952), a New York lawyer, who published a number of biblio essays on various topics. Notably, he contributed to The Colophon New Series, Vol. II, No. 4, 1937, “A Five-Foot Shelf of Literary Forgeries.” In The Colophon “Notes on Contributors” we read, “Mark Holstein is president of the Quarto Club. He describes himself as an aging lawyer, who started collecting books in his teens and has kept it up with unflagging zeal for almost fifty years. He has collected more books than he will ever be able to read, and has a separate room devoted to Shakespeariana. If all the time he has spent in reading and marking [auction / bookseller] catalogues were placed end to end, it would reach far enough to round out several college careers.”

Then a little voice talks to me, a faint recall, and I look in my own library catalogue and behold! I find I have Holstein’s pamphlet The Diversions of a Will Collector (1929), a paper read to the Quarto Club in New York City, this copy inscribed to none other than legendary bookseller A.S.W. Rosenbach, “To Dr. R, with the season’s greetings and the compliments of the author.”

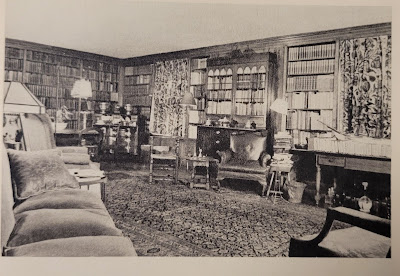

The association copy excitement I’m feeling now is rising quicker than my homemade pizza dough. There is more to explore with Holstein. I find a photograph of his library illustrated in another issue of The Colophon; I want to know about the Quarto Club he founded; I want to read more of his writings, but such byways will be pursued later. For now, this enthusiastic original owner of The Greatest Book in the World has been rediscovered if not fully resurrected. As to the dispersal of his library, the New York Times obituary of Oct. 19, 1952 records, “His will provides for distribution of his library among various public libraries.” I also discover that “The Fine Library of Mark G. Holstein, Attorney at Law, New York City,” was sold by Swann Galleries in 1953. I have yet to see its contents.

|

| Mark G. Holstein library, ca. 1937 |

But I can hazard a guess that at Holstein’s sale, if not earlier, Montgomery Evans II (1901-1954), the second owner of the book, acquired this copy. His bookplate is neatly placed under Holstein’s. Montgomery Evans collected British author Arthur Machen with fervor as Vincent Starrett records in his autobiography, Born in a Bookshop. I find references elsewhere to Evans’ collection of Anglo-Irish writer Lord Dunsany. Evans knew Machen personally and wrangled letters and manuscript material from his favored authors. His ownership of this book was apparently a short-lived union, however, for Evans died in 1954, only a year after the Holstein auction. But his time spent was a memorable experience. In faint pencil on the rear pastedown Evans was moved to record and initial the following, “Read with great pleasure on Sundays in New York, May 1953.” This simple note touched me. Could Newton have asked for a more concisely satisfying review?

From Evans the book found its way into the library of Abel Berland (1915-2010), a Chicago real estate magnate, who as young Jewish man experienced discrimination and hardship, yet in Horatio Alger fortitude garnered a law degree and rose to the heights of business. Berland collected an exceptional library of English literature, incunabula, science, and philosophy. The highspots of this collection, including a fine set of the Four Folios of Shakespeare, were auctioned by Christies in October 2001 and brought $14,391,678. (The books would have certainly sold for even more had the events of 9/11 not happened shortly before the sale.) Yet Berland’s collection contained many more books than his expensive rarities. By all accounts, he loved to deep-dive into the history and scholarship of his collection, and he was a voracious reader of biblio-books. This provided inspiration and gave him a sense of place in the long history of book collecting.

|

| Abel E. Berland |

Berland was devoted to Chicago’s The Caxton Club, a highly regarded organization of bibliophiles established in 1895. Berland serving a term as president and recruited many new members. He was frequently featured in the Club’s journal, the Caxtonian. After his death, the April 2011 issue of the Caxtonian was dedicated to Berland and contained many reflections by people who knew him well.

Fellow collector R. Eden Martin remembered Berland’s friendship and guidance, “Abel Berland was Chicago’s greatest book collector. Others have magnificent collections and are outstanding scholars in their fields. But Abel brought together wonderful books from a wide variety of literature and thought: copies of masterpieces of English literature. . . books from the early years of printing with movable type, and books of science and intellect. . . .”

“Abel would tell how as a child, after his parents had told him to turn out the light and go to sleep, he would read in bed with a special light. Or how, as a young man, he would bring home a book in its wrappings and place it outside a window in his house, so he could smuggle it in without having to provide an explanation. . . .”

“Abel introduced me to two prominent American dealers. He set up a lunch for me with a handful of Chicago’s notable collectors. He regularly sent me copies of pages from auction catalogues. He spread his enthusiasm like a virus, which in a way it was. He helped me grow from an accumulator into a collector.”

Robert Cotner, another close friend, recalled a particular visit, “The [library] room,” Abel said that day, “is my library of the mind, the habitation of books literary, scientific, and historical that I consider important. I often read into the night and am stimulated by the great ideas of these remarkable people.”

The ample bookplate of Abel Berland in Newton’s The Greatest Book in the World largely covers—nay, overshadows—the earlier Holstein and Evans bookplates. It features a photograph captioned, “A Frank Lloyd Wright designed bridge as viewed from our library window.” Heady stuff, but did Berland really read the book as he enjoyed the view? Did he spend time with it as Holstein and Evans had and draw biblio-nourishment from the contents? I wondered as much as I closely examined the book. The answer came on the rear pastedown, just below Montgomery Evans’ faint penciled note, Berland had added his own, “Read in November 1968, and again in August 1981, and in April 97.”

I then began my own re-reading that bright morning, holding the book as the others before me, pausing occasionally to view our spring yard in bloom with fresh foliage courtesy of Nicole’s efforts, the sharp sounds of birds and squirrels, and the focused efforts of our new cat, Ziggy, doing his best to hunt them, and realizing it was not unlike my pursuit of books.

Dedicated to the memory of my friend and fellow bibliophile, Jerry Morris (1947-2022)

As always just wonderful Kurt. Wonderful. And the dedication to Jerry perfect and touching; he is and will be missed- the subject (Newton) and the ties thereto are something Jerry would have enjoyed and greatly appreciated. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteAnd not just Newton....tying in Berland was fantastic. it is all about the 'stories' and you tell them wonderfully!

DeleteGreat story, great photos. I love the pic of Berland in his smoking jacket (?) with his books, mirroring the gesture of the little figurine on the table (Shakespeare?). He looks to have had a sense of humor. Also, what a lovely picture of Jerry you chose!

DeleteI have just purchased a good copy with DJ of William Dana Orcutt's In Quest of the Perfect Book (1926). It lacks his signature but I am anticipating a pleasurable read!

Kurt, As usual you touch on a lot of the same feelings I get when I'm reading a book that's been in the hands of others I hold in awe or high regard. I also like the fact that these books have some battle scars and marginalia.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the inclusion of the Jerry Morris dedication.

Tom S.

Thanks, Kurt. Your piece had everything this bookman could desire: tribute to Jerry, Newtonian lore, great associations, Shakespeare folios, and Nicole's flowers.

ReplyDeleteTerry S.

Was googling Mark Holstein and found this essay. I am new to collecting but have read and enjoyed your recent book Kurt. I just purchased a copy of Fletcher’s English Collectors (1902, London - part of English Bookman’s Library) and it has Mark’s bookplate in it. Very cool to learn more about him. I also was at the FL fair where Jerry passed sadly. I had just met him the day before actually.

ReplyDelete