|

| The Book Fellows Bookplate |

I haven’t done this much clubbing since college. But that is a far different story involving an energetic redhead, the thumping bass of dance music, and my free-form dancing skills that generated much laughter. Thankfully, no videos exist. But I digress. My recent excursion into the history of the Quarto Club of the 1920s-30s involved no such risk of injury or embarrassment. It was a pleasurable way to resurrect a nearly forgotten group of dedicated bibliophiles. But just as in those memorable college days, one clubbing experience was rarely enough and I was left wanting more. I pushed back further in time in my research, still New York City, but now the early 1880s. I recalled a book first spotted online years earlier, its importance not realized at the time. And thank the book gods it was still available!

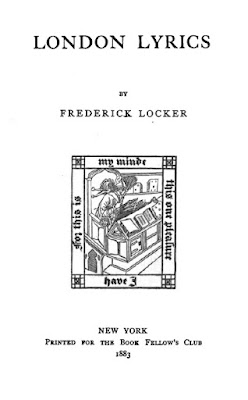

I have on my desk now Frederick Locker’s London Lyrics (NY: 1883) the first publication of The Book Fellows’ Club (est. 1881), a tiny but influential wellspring that served as the genesis of the Grolier Club of New York, founded in 1884. Their club consisted of but three official members: the founder, Valentin[e] Blacque, and two biblio-friends William Loring Andrews and Alphonse Duprat. Their history is fragmentary and scattered, but not lost. They left us two imprints and a story.

We begin with Adolph Growoll, indefatigable biblio-historian, who writes in American Book Clubs (1897), “In 1881 several book-lovers were in the habit of meeting at each other’s houses, to compare notes and books, criticize each other’s treasures and new purchases, to dine together and talk over their one hobby. Out of these gatherings grew The Book Fellows’ Club. It was from the beginning, and remained until the end, a purely social and sociable organization. It had no constitution nor by-laws, nor any charter. . . It was proposed to enlarge the club by the admission of many more members, among whom there seemed to be some whose qualifications for membership were open to doubt, and it was decided not to make such a formal affair of The Book Fellows’ Club as would necessarily result from such an increase. This reluctance, in a measure, led to the formation of the Grolier Club. In the shadow of this larger, more completely-organized, and wealthier organization the ‘Book Fellows’ took a back seat—so far back, in fact, that they only continued to be sociable and published no more books.”

More details are found in the earliest published account of the Book Fellows by Henri Pene du Bois (1858-1906), who knew the members personally. Pene du Bois, an American educated in France, was an ardent bibliophile, art critic, newspaper man, and flamboyant writer. The art and history of bookbinding was a particular interest. He is most remembered as the author of Four Private Libraries of New-York (1892), with one of the featured libraries being Valentine Blacque’s. He also authored American Book Bindings in the Library of Henry William Poor (1903). (We will meet Mr. Poor later.) Pene du Bois’ essay, “The Book Fellows’ Club,” appeared under the pseudonym of David Gamut in the September 8, 1889 New York Times. He writes:

“In 1883, when the lilacs were in bloom, the studious quarter of the Astor Library, Murray Hill, destined to be the most famous of patrician hills for its marvelous Grolier Club, Andrews, Avery, Hoe, and Ives Libraries, and every shop where two book fanciers meet, were conquered, invaded, and taken by a young bibliophilist as was Buda by Soliman in 1526. He did not commit this crime alone; he had accomplices; but they bore the impenetrable legend of The Book Fellows’ Club, and as usually happens when imagination takes the place of reality, passed for an army larger than the famed one of Xerxes. The truth is stranger, for the truth is that Mr. Valentin Blacque, being possessed with much artistic discernment, an ardent love for books, and an impatient desire for more treasures than came of the Hotel Drouot and Sotheby’s, one fine day invited to dinner Messrs. W. L. Andrews and A. Duprat, and there delivered a speech which is lost to the records of bibliomania, but may be reconstructed in tenor, if not in exact diction, from the memory of its two auditors.

“[Blacque] said that it would take longer than they could wait to found a club of a hundred book lovers without a publisher, bookseller, printer, or bookbinder, estimable people, but directly interested in the making of books. Then, that he was the founder and only member of a club called the Book Fellows, which at its first meeting made him President, as was his due; Treasurer, as was his penalty, and Secretary, executive, membership, and publication committees as was his pleasure. If they desired to become members he would pass upon their application at once. No initiation fee was required, but they were expected to share proportionately in the expense of the publication of the first book, which would be [Frederick] Locker’s ‘London Lyrics.’ A month after came a portrait, a book-plate, and a poem in manuscript of Locker, and at the third dinner, two months later, the only officer of The Book Fellows’ Club presented to its two members bills of the bookmakers for $560—public interest absolutely requires this indiscretion—in settlement whereof every one drew his check for $186.66. . . In 1884, the second publication of The Book Fellows’ Club took the form of a square 12mo, bound temporarily, uncut, in blue cloth, entitled, ‘Songs and Ballads by Edmund Clarence Stedman,’ and illustrated by Bowlend. The entire edition of 100 copies was printed on Japan paper. . .

“Since then the Grolier Club has come and grown to one of the most influential clubs in the world; Mr. W. L. Andrews is the President; the Aldine has made a mark, and the prefatory poet [Henry C. Bunner] of ‘Songs and Ballads’ is one of its Directors. . . but The Book Fellows’ Club is not dormant. It sits at its library table, under a ceiling made of a gigantic Grolier binding, invokes the gods of India, Egypt, and other countries whose name it knows, to let it be modern, original, and American, plots to that end, and will make another conquest of all who dearly love the love of books, after its next dinner meeting.”

Now that is a description, and it only gets more entertaining when Pene du Bois and Blacque rejoin us below. But first let us background the other two members.

William Loring Andrews (1837-1920) is the most well-known of the Book Fellows. His general fame as a collector and author of many privately printed biblio-books is not our topic now, so I’ll limit his appearance to a relevant excerpt. Walter Gilliss writes in Transactions of the Grolier Club (1921), “In any reference to the [Grolier] Club’s early days, the first name that instinctively comes to mind is that of William Loring Andrews, our second president, whose name has always stood at the head of the list of Founders. . . It was in his mind that there germinated the seed of the idea from which the [Grolier] Club sprang, and it was by him that the writer was told long ago that he was one of a little company of men, who, as early as the autumn of 1883, held meetings, having in mind the establishing of a Reading or Book Club. . . It seems appropriate to record here, that the little company of bibliophiles of which Mr. Andrews had been a member shortly before the founding of the ‘Grolier,’ and to which he often referred, was known as The Book Fellows’ Club, and that it issued two books.”

|

| William Loring Andrews |

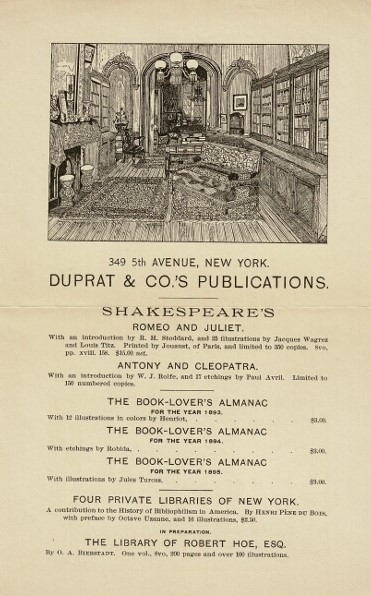

The second Book Fellows member Alphonse Duprat (1843?-1897), born in Holland, was a bibliophile, dealer, and publisher who started out as a Wall Street banker and spent much of his life in New York City. Duprat would publish several important biblio-books, notably the five volumes of The Book-Lover’s Almanac (1893-1897), Pene du Bois’ Four Private Libraries of New-York (1892), and O.A. Bierstadt’s The Library of Robert Hoe (1895).

The last volume of Duprat’s The

Book-Lover’s Almanac was announced in The Critic of May 8,

1897, “The fifth volume of this truly artistic annual visitor lies before

us. Its publication preceded by but a

few months the death of its founder, Alphonse Duprat, who was happy nearly all

his life, in that his profession was his avocation as well: for he was

booklover by predilection and a bookseller and publisher by trade. Born in Amsterdam, Holland, only fifty-four

years ago, Mr. Duprat originally came to this country to found a branch of his

father’s bank. His uncle had been a

well-known collector of books and bric a-brac.

Mr. Duprat, soon after his arrival, entered the firm of Jay Cooke &

Co. as confidential man. Upon its

failure he cast about for some agreeable occupation in keeping with his tastes

and desires and entered into partnership with Mr. George J. Coombes as dealers

in books. Subsequently he ran the

business alone. His shop was a resort

for book-lovers of the nicest tastes, and his publications were eagerly sought

after by the wary collector. His taste

in the fine art of book-making was most true, and both the collector and lover

of the beautiful have lost a real enthusiast in his death, which took place on

March 27.”

Henri Pene du Bois writes of Duprat in the Dec. 8, 1895 New York Times, “[He] was, until Pan visited Wall Street, a banker, an ardent book lover, the most active encourager of native artisans in furniture, pottery, bookmaking and bookbinding, rugs of Persia, magnificent tulips, unknown ivories, extraordinary books, and lived in an atmosphere of art, consulted in matters of taste, and regarded with reverence by experts and great collectors. When his bank failed and he became an invalid, motionless except in the expression of his eyes, he continued to be a Maecenas, not with money, but with ideas. He was one of the founders of The Book Fellows’ Club, and the new spirit of book collecting inspired him as soon as it revealed itself to anybody. He presided over the development of private libraries of his friends with as much interest as if they were his own.”

We’ll finish the sketch of Alphonse Duprat by inviting him to speak to us first-hand via the February 10, 1900 New York Times:

“No reasoning or argument will deter the real book-lover from his charming pursuit. The love of books and their possession are to him pleasures that the man who reasons about their utilitarianism cannot feel, and his very argument is the best proof that he lacks the feu sacre [sacred fire] of the real book-lover.

“The collecting of books is pre-eminently the highest form of collecting, involving as it does more aesthetic pleasure than either the collecting of paintings, statuary, bric-a-brac, porcelains, or tapestry, against the folly of which no essays have ever been written. A book appeals to the intelligent collector not only by the art of the author, be it prose or poetry, but also by the skill of the printer, the taste of the illustrator, and finally, by the art of the binder, and if to these are added the charm of provenance, or a dedication, or a fine ex-libris, you have a combination of pleasures not to be found in any other object within the domain of collectorship.”

Finely stated, Mr. Duprat. You may be seated. Now we have come to The Book Fellows’ Club founder, Valentin[e] Blacque (1851-1915), a New York City stockbroker, book collector, amateur artist, and musician. He was one of the early American collectors of contemporary French book design. Blacque’s multiple interests reflect his varied background. He was born in France of an American mother from the prominent Mott family, and a Turkish father. He spent his early years in Paris. His father, Eduard Blacque, later became a Turkish diplomat stationed in Washington, D.C. Valentine Blacque’s French roots stayed planted his entire life, permeating his avocations both bookish and otherwise, but he was primarily schooled in the United States, a graduate of Columbia University, and spent his adult years working on Wall Street in New York City before retiring in France. This theme of Wall Street work runs through the lives of many of these bookmen. An exploration for another time.

You’ll recall Pene du Bois’ early description of the Book Fellows gathering in a splendid room with a ceiling “made of a gigantic Grolier binding.” A nice touch, surely metaphorical. But no, it was not! For Pene du Bois writes in Four Private Libraries of New-York this more lavish description of Valentine Blacque’s library:

“The Trianon of a book-lover, coquettish as the Queen’s. A room the ceiling of which, in red Morocco of the Levant, reproduces exactly the color, harmonious lines, and lyrical flight into azure of a wing of a book bound for Grolier. Tapestry of Beauvais; etchings of Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Visscher, Fortuny, and Lalanne; original drawings by Leloir, Du Maurier, Kate Greenaway, Blum, Chase, and Taylor; bookcases the crystal panes in the dark oak doors of which are lozenged. . . At the table, carved in massive oak, on a Persian carpet of silk, in a casket of lapiz-lazuli, pell-mell with the rubies, diamonds, sapphires, and emeralds, the treasure of the reliquary, a book of poems not to be described, illuminated by cherished artists with fugitive rays of sunlight, flame of eyes, and blushing pink of lips. . . For there are no books in the cases not ardently loved; none prized because scarce although ugly; none admitted because necessary to a set or indispensable to a system. They are beautiful, and they have not a double elsewhere. All converge to the blue diamond book of poems of the reliquary in beauty and art. It is not an accomplishment that may be lightly given as an example to others. It is like drawing the bow of Ulysses, a feat of Ulysses impossible to our frail arms.”

Pene du Bois might have been enjoying a wee bit of absinthe during writing time, but the imagination does run rampant contemplating this bookroom. It is a shame indeed that no photograph appears to survive of Mr. Blacque’s library.

Pene du Bois was not the only one impressed. Famed French bibliophile Octave Uzanne visited New York City in 1893. Willa Silverman records in The New Bibliopolis: French Book Collectors and the Culture of Print, 1880-1914 (2008), “Uzanne found in the private libraries of Blacque and other American book collectors ‘the best works of the present time, in extraordinary states, and bindings conceived in accordance with the exact principles that I have enunciated.’ His stay in the United States convinced him that, far from being indifferent and unsophisticated as he had expected, American book lovers were in fact in many ways superior to their Parisian counterparts.”

Glimpses of Blacque in the newspapers outline his character. The March 27, 1904 New York Times records, “Vale Blacque. . . is a well-known member of the Knickerbocker Club. He is quite a picturesque-looking personage on Fifth Avenue. He is very tall, and usually dresses in gray, and has the cast of countenance of the operatic Mephisto. But Mr. Blacque is one of the most genial of men. He is a collector of books and has one of the best selected libraries in town, and is an excellent musician and composer.”

Another glimpse is found in the New York Times of March 18, 1906 after Blacque’s retirement. He and his wife are spending much time in Paris, “Valentine Blacque has been in Paris and Mrs. Blacque goes over to be with him. At present he is making much success with the binding of books, an art and fad much in vogue on the other side. . . [he] was for years a well-known figure in New York society. . . He composed a mass which was sung at the Church of St. Francis Xavier, and a number of songs. Mrs. Blacque was Miss Kate Read. Both she and her husband have a wonderful gift as raconteurs.”

This raconteuring couple must have been fun to spend time with. One of their circles of friends was fellow Wall Street advisor Henry W. Poor and his wife. Poor (1844-1915) was a fully immersed bibliophile, one of the great book collectors of his time, well-funded and apparently persuasive. Coinciding roughly with Blacque’s retirement in 1903, Poor purchased Blacque’s Cabinet Library consisting of seventy-two carefully chosen volumes for the mighty sum of $25,000 [approximately $850,000 today]. Poor’s enthusiasm over the purchase soon resulted in the publication of a Catalogue of the “V[alentine]. A. B[lacque].” Collection in the Library of Henry W. Poor. (1903). Fortunately for us, Blacque’s letter to Poor about his collection is reproduced and gives insight into Blacque’s approach to collecting and his sentimental leanings:

New York, March 14, 1903

My

Dear Poor,

I am tremendously flattered at the thought that you are to make a separate catalogue of my books. I have brought them together with a great deal of pleasure, have lived with them and loved them. I have endeavored from time to time, to make them more interesting and valuable by adding documents, prints, autograph letters—when possible I have secured a volume which is unique. By a ‘unique book’ I mean one which cannot under any circumstances be duplicated. The mere insertion of autograph letters or portraits does not seem to me enough to render a book worthy of the title -- unique. But the original drawings of the illustrator of the book, or a series of drawings made especially for it and inserted must stamp it as the only one of its kind. Another feature which I have tried to carry out is the historical interest (to a book-lover) of the volume itself. It seems to me a decided attraction to a book that it has stood on the shelves of one of the bibliophile epicures of the time past. The men who were the patrons of the writers, printers and bookbinders, choose for themselves the best, and the knowledge that such a volume figured in their catalogue, bears on the fly leaf their book-plates and has since belonged to other collectors of note, marks it as being worth having. . . It is a historical document with a title of nobility justly earned.

It is a pleasure to know that you will keep them together in one case, alongside of each other. I have kept them so long and so closely together that it seems to me as if they would mourn if separated. I love to cherish the fancy that my favorite authors with their Heroes and Heroines and the owners, too, of the books they cherished so fondly, left something of their personalities between the leaves and in the binding; and that at some quite midnight hour, they would walk out and flock together and talk matters over, discuss the failings and foibles of their present owner, the comforts or discomforts of their abiding place. . .

Yes, I am glad you will keep them together, thank you for that, and again for the compliment you have paid me.

Faithfully yours,

V.A.B.

Henry W. Poor was at the peak of his

collecting when he purchased the Blacque books.

However, Dickinson writes in Dictionary of American Book Collectors,

“Poor’s own financial career was marked with spectacular successes and equally

spectacular failures. . . In 1908, when Poor’s financial structure collapsed,

Arthur Swann of the Anderson Auction Company prepared a sumptuous sale catalog

calculated to pull large bids out of sensitive buyers. . . a new collector, Henry E. Huntington, took

away most of the prizes. With the

irrepressible book dealer George D. Smith leading the way, Huntington managed

to capture almost one-third of the Poor library.”

Arthur Swann’s (?) anonymous introduction to Catalogue of the Library of Henry W. Poor Part V (April 6-9th, 1909), highlights Blacque’s books and explains the French-influenced idea of a Cabinet collection:

“A feature of the highest interest is a small but remarkable collection of Association and Illustrated Books originally formed by Valentine A. Blacque and by him transferred to Mr. Poor. There are only 72 titles in the collection, but each item challenges attention on account of its extreme rarity and value.

“To understand the collection properly, one must measure it by a standard of the leading French collectors, in whose ranks are found the most critical connoisseurs and perhaps the best judges. With them quality and not quantity is the desideratum. A small bookcase, ‘Le Cabinet,’ holding from fifty to one hundred and fifty volumes is the usual feature, in which are preserved the jewels of the collection, and other books of not so great importance are relegated to the shelves of the library, if the owner possesses one, though most men are content with ‘Le Cabinet’ alone. Baron Rothschild had a small cabinet holding one hundred and twenty volumes valued at more than half a million francs; Baron Pichon had one of the same size and nearly as valuable, as had also the Baron Portalis. Charles Nodier’s Cabinet was composed wholly of the rarest and finest Elzevirs to be procured; and the Valentine Blacque collection is in the same category—indeed many of the books were secured at the dispersal of some of the Cabinets mentioned.”

|

| Promotional flyer, ca. 1895 |

Henri Pene du Bois writes of Duprat in the Dec. 8, 1895 New York Times, “[He] was, until Pan visited Wall Street, a banker, an ardent book lover, the most active encourager of native artisans in furniture, pottery, bookmaking and bookbinding, rugs of Persia, magnificent tulips, unknown ivories, extraordinary books, and lived in an atmosphere of art, consulted in matters of taste, and regarded with reverence by experts and great collectors. When his bank failed and he became an invalid, motionless except in the expression of his eyes, he continued to be a Maecenas, not with money, but with ideas. He was one of the founders of The Book Fellows’ Club, and the new spirit of book collecting inspired him as soon as it revealed itself to anybody. He presided over the development of private libraries of his friends with as much interest as if they were his own.”

We’ll finish the sketch of Alphonse Duprat by inviting him to speak to us first-hand via the February 10, 1900 New York Times:

“No reasoning or argument will deter the real book-lover from his charming pursuit. The love of books and their possession are to him pleasures that the man who reasons about their utilitarianism cannot feel, and his very argument is the best proof that he lacks the feu sacre [sacred fire] of the real book-lover.

“The collecting of books is pre-eminently the highest form of collecting, involving as it does more aesthetic pleasure than either the collecting of paintings, statuary, bric-a-brac, porcelains, or tapestry, against the folly of which no essays have ever been written. A book appeals to the intelligent collector not only by the art of the author, be it prose or poetry, but also by the skill of the printer, the taste of the illustrator, and finally, by the art of the binder, and if to these are added the charm of provenance, or a dedication, or a fine ex-libris, you have a combination of pleasures not to be found in any other object within the domain of collectorship.”

Finely stated, Mr. Duprat. You may be seated. Now we have come to The Book Fellows’ Club founder, Valentin[e] Blacque (1851-1915), a New York City stockbroker, book collector, amateur artist, and musician. He was one of the early American collectors of contemporary French book design. Blacque’s multiple interests reflect his varied background. He was born in France of an American mother from the prominent Mott family, and a Turkish father. He spent his early years in Paris. His father, Eduard Blacque, later became a Turkish diplomat stationed in Washington, D.C. Valentine Blacque’s French roots stayed planted his entire life, permeating his avocations both bookish and otherwise, but he was primarily schooled in the United States, a graduate of Columbia University, and spent his adult years working on Wall Street in New York City before retiring in France. This theme of Wall Street work runs through the lives of many of these bookmen. An exploration for another time.

You’ll recall Pene du Bois’ early description of the Book Fellows gathering in a splendid room with a ceiling “made of a gigantic Grolier binding.” A nice touch, surely metaphorical. But no, it was not! For Pene du Bois writes in Four Private Libraries of New-York this more lavish description of Valentine Blacque’s library:

“The Trianon of a book-lover, coquettish as the Queen’s. A room the ceiling of which, in red Morocco of the Levant, reproduces exactly the color, harmonious lines, and lyrical flight into azure of a wing of a book bound for Grolier. Tapestry of Beauvais; etchings of Rembrandt, Van Dyck, Visscher, Fortuny, and Lalanne; original drawings by Leloir, Du Maurier, Kate Greenaway, Blum, Chase, and Taylor; bookcases the crystal panes in the dark oak doors of which are lozenged. . . At the table, carved in massive oak, on a Persian carpet of silk, in a casket of lapiz-lazuli, pell-mell with the rubies, diamonds, sapphires, and emeralds, the treasure of the reliquary, a book of poems not to be described, illuminated by cherished artists with fugitive rays of sunlight, flame of eyes, and blushing pink of lips. . . For there are no books in the cases not ardently loved; none prized because scarce although ugly; none admitted because necessary to a set or indispensable to a system. They are beautiful, and they have not a double elsewhere. All converge to the blue diamond book of poems of the reliquary in beauty and art. It is not an accomplishment that may be lightly given as an example to others. It is like drawing the bow of Ulysses, a feat of Ulysses impossible to our frail arms.”

Pene du Bois might have been enjoying a wee bit of absinthe during writing time, but the imagination does run rampant contemplating this bookroom. It is a shame indeed that no photograph appears to survive of Mr. Blacque’s library.

Pene du Bois was not the only one impressed. Famed French bibliophile Octave Uzanne visited New York City in 1893. Willa Silverman records in The New Bibliopolis: French Book Collectors and the Culture of Print, 1880-1914 (2008), “Uzanne found in the private libraries of Blacque and other American book collectors ‘the best works of the present time, in extraordinary states, and bindings conceived in accordance with the exact principles that I have enunciated.’ His stay in the United States convinced him that, far from being indifferent and unsophisticated as he had expected, American book lovers were in fact in many ways superior to their Parisian counterparts.”

Glimpses of Blacque in the newspapers outline his character. The March 27, 1904 New York Times records, “Vale Blacque. . . is a well-known member of the Knickerbocker Club. He is quite a picturesque-looking personage on Fifth Avenue. He is very tall, and usually dresses in gray, and has the cast of countenance of the operatic Mephisto. But Mr. Blacque is one of the most genial of men. He is a collector of books and has one of the best selected libraries in town, and is an excellent musician and composer.”

Another glimpse is found in the New York Times of March 18, 1906 after Blacque’s retirement. He and his wife are spending much time in Paris, “Valentine Blacque has been in Paris and Mrs. Blacque goes over to be with him. At present he is making much success with the binding of books, an art and fad much in vogue on the other side. . . [he] was for years a well-known figure in New York society. . . He composed a mass which was sung at the Church of St. Francis Xavier, and a number of songs. Mrs. Blacque was Miss Kate Read. Both she and her husband have a wonderful gift as raconteurs.”

This raconteuring couple must have been fun to spend time with. One of their circles of friends was fellow Wall Street advisor Henry W. Poor and his wife. Poor (1844-1915) was a fully immersed bibliophile, one of the great book collectors of his time, well-funded and apparently persuasive. Coinciding roughly with Blacque’s retirement in 1903, Poor purchased Blacque’s Cabinet Library consisting of seventy-two carefully chosen volumes for the mighty sum of $25,000 [approximately $850,000 today]. Poor’s enthusiasm over the purchase soon resulted in the publication of a Catalogue of the “V[alentine]. A. B[lacque].” Collection in the Library of Henry W. Poor. (1903). Fortunately for us, Blacque’s letter to Poor about his collection is reproduced and gives insight into Blacque’s approach to collecting and his sentimental leanings:

New York, March 14, 1903

I am tremendously flattered at the thought that you are to make a separate catalogue of my books. I have brought them together with a great deal of pleasure, have lived with them and loved them. I have endeavored from time to time, to make them more interesting and valuable by adding documents, prints, autograph letters—when possible I have secured a volume which is unique. By a ‘unique book’ I mean one which cannot under any circumstances be duplicated. The mere insertion of autograph letters or portraits does not seem to me enough to render a book worthy of the title -- unique. But the original drawings of the illustrator of the book, or a series of drawings made especially for it and inserted must stamp it as the only one of its kind. Another feature which I have tried to carry out is the historical interest (to a book-lover) of the volume itself. It seems to me a decided attraction to a book that it has stood on the shelves of one of the bibliophile epicures of the time past. The men who were the patrons of the writers, printers and bookbinders, choose for themselves the best, and the knowledge that such a volume figured in their catalogue, bears on the fly leaf their book-plates and has since belonged to other collectors of note, marks it as being worth having. . . It is a historical document with a title of nobility justly earned.

It is a pleasure to know that you will keep them together in one case, alongside of each other. I have kept them so long and so closely together that it seems to me as if they would mourn if separated. I love to cherish the fancy that my favorite authors with their Heroes and Heroines and the owners, too, of the books they cherished so fondly, left something of their personalities between the leaves and in the binding; and that at some quite midnight hour, they would walk out and flock together and talk matters over, discuss the failings and foibles of their present owner, the comforts or discomforts of their abiding place. . .

Yes, I am glad you will keep them together, thank you for that, and again for the compliment you have paid me.

Faithfully yours,

V.A.B.

|

| The Library of Henry W. Poor, New York City |

Arthur Swann’s (?) anonymous introduction to Catalogue of the Library of Henry W. Poor Part V (April 6-9th, 1909), highlights Blacque’s books and explains the French-influenced idea of a Cabinet collection:

“A feature of the highest interest is a small but remarkable collection of Association and Illustrated Books originally formed by Valentine A. Blacque and by him transferred to Mr. Poor. There are only 72 titles in the collection, but each item challenges attention on account of its extreme rarity and value.

“To understand the collection properly, one must measure it by a standard of the leading French collectors, in whose ranks are found the most critical connoisseurs and perhaps the best judges. With them quality and not quantity is the desideratum. A small bookcase, ‘Le Cabinet,’ holding from fifty to one hundred and fifty volumes is the usual feature, in which are preserved the jewels of the collection, and other books of not so great importance are relegated to the shelves of the library, if the owner possesses one, though most men are content with ‘Le Cabinet’ alone. Baron Rothschild had a small cabinet holding one hundred and twenty volumes valued at more than half a million francs; Baron Pichon had one of the same size and nearly as valuable, as had also the Baron Portalis. Charles Nodier’s Cabinet was composed wholly of the rarest and finest Elzevirs to be procured; and the Valentine Blacque collection is in the same category—indeed many of the books were secured at the dispersal of some of the Cabinets mentioned.”

By the time of the Henry W. Poor auction, Blacque

was happily retired in Paris, still buying a book or two that proved

irresistible, and apparently trying his own hand at bookbinding. His life of books ended prematurely in 1915 amid

World War I while helping others, “Blacque. . . since the outbreak of the

European war, had been assisting the American ambulance work in Paris, is dead

at his home at Rue Pierre Charron. His

illness [pneumonia], it was reported, was brought on by overwork among the war

sufferers.”

Blacque’s carefully selected library represented the significant French influence among American bibliophiles of the period. But his cabinet collection was scattered involuntarily into the “vast azure” even before his death. Blacque’s lasting legacy is the founding of The Book Fellows’ Club, three sympatico bookmen dining at his home under a Grolier-esque ceiling, Blacque’s Cabinet of Books close at hand, good talk among raconteurs, perhaps Blacque’s wife joining in the exchange, one book, then two, produced by these Book Fellows, and a bigger moment springing forth and the Grolier Club soon formed.

Despite Blacque’s prominence as a book collector and bibliophile over the following two decades (ca. 1884-1904), it remains unknown why he never became a member of the Grolier Club like his other two Book Fellows. History incomplete, but not forgotten.

Blacque’s carefully selected library represented the significant French influence among American bibliophiles of the period. But his cabinet collection was scattered involuntarily into the “vast azure” even before his death. Blacque’s lasting legacy is the founding of The Book Fellows’ Club, three sympatico bookmen dining at his home under a Grolier-esque ceiling, Blacque’s Cabinet of Books close at hand, good talk among raconteurs, perhaps Blacque’s wife joining in the exchange, one book, then two, produced by these Book Fellows, and a bigger moment springing forth and the Grolier Club soon formed.

Despite Blacque’s prominence as a book collector and bibliophile over the following two decades (ca. 1884-1904), it remains unknown why he never became a member of the Grolier Club like his other two Book Fellows. History incomplete, but not forgotten.

So you now have a plan for the Zimmerman Library decor - a Grolier ceiling! Also a next writing project- what is in the KZ Cabinet of Books? Very interesting essay as always

ReplyDeleteI agree with Bill - seems like you and Blacque had a lot in common. Finally got a chance to read your book and found it very entertaining. Hope to catch up with you soon!

ReplyDeleteA tale well told. So, what was in Blacque's Cabinet of Books?

ReplyDelete